The (Complicated) Simple Joy of Stardew Valley

Or, How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love The Farming Simulator.

Note: May contain spoilers of aspects of the game’s plot.

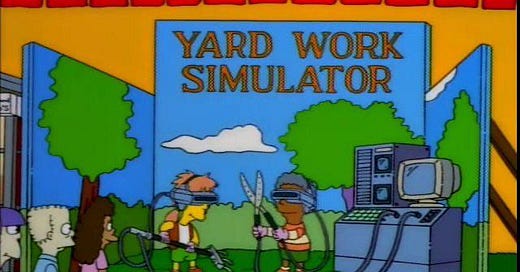

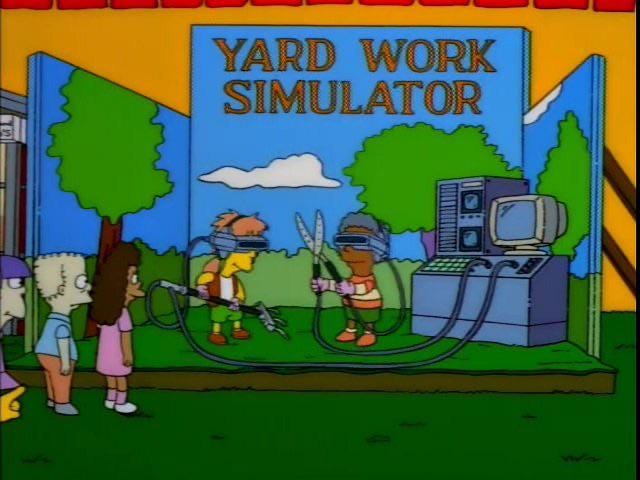

When it comes to computer games, I’ll never pretend to be anything less than obsessive. I was raised by the Sony Playstation and Sega Mega Drive, and my fingers and thumbs have had callouses from button inputs for as long as I can remember. On the school playground I’d run around by myself, pretending I was flaming gnorcs and collecting treasure just like Spyro The Dragon. In around 2006, we managed to acquire a copy of The Sims 2 Pets for the Playstation 2, and immediately, the life simulation genre had sunk its tendrils into me. I’d actually get up early in order to play before school, and, before long, whilst scouring the internet on the family computer, I learned of the PC counterpart. I played The Sims 2 so much that, one fateful summer, I actually developed bedsores. I still adore the series to this day, though even The Sims 2 doesn’t quite feel the same now I’m a grown-up myself. It was 2006, too, that I received Harvest Moon DS for Christmas, a farming simulator, though at this stage I cared much more about wooing the local barmaid with jewellery I dug up in the mines. Whenever I tired of my Sims, Harvest Moon was there, providing another escape by way of a kind of alternate universe.

Harvest Moon, now named Story of Seasons after a split between developers, would too capture the heart of one Eric Barone, known as ConcernedApe. He felt, though, the series had gradually decreased in quality after 1999’s Harvest Moon: Back To Nature, and was frustrated at the lack of alternatives that addressed the shortcomings of the series. So, he did what any other aspiring game designer would, and began work on his own game. Over the course of four and a half years, Barone painstakingly crafted an entire world, a compelling overarching storyline, complex and nuanced characters and game mechanics, and did it all himself. Barone even drew the character portraits and composed the game’s soundtrack. He called his project Stardew Valley, and I, for one, can’t stop playing, and it’s becoming a problem. One I’m not sure I want to fix. In under a week, and whilst juggling a full-time job and several writing deadlines, I’ve finished my first year in-game, and made a huge dent into my second. I’ve found myself having dreams about it. I spent, actual, real money - four of your English pounds - for the Mobile version so I could have another save to play on whilst out and about. Despite playing on Switch. I played so much, in fact, that my controller broke. Sort of. So, I’m going to tell you all about my farm, my foppish long-haired fictional boyfriend, and why we’re so compelled by this game eight years on.

I’ve dipped in and out of Stardew Valley since around my second year at University, when I downloaded it for my Switch with the £20 E-Shop voucher bundled with the console. Really, I think I was looking for something to fill the void that waiting for a new installment of Animal Crossing had left, and once New Horizons was indeed released the following year, any lifelong fans can remember how that went. Spoiler: it was not well. I enjoyed it well enough, but, of course, I was twenty, and the infinitely more exciting pursuits of real boys, boozing and sourcing duty-free Silk Cut from down the pub appealed slightly more than sitting in front of the telly tending to a virtual farm. My housemates at the time, also big gamers, arguably more than myself, sung its praises. “Oh, it’s excellent! Just wait till you get to the third year!” I liked it. I thought the dialogue was funny, and the 16-bit visual style was just adorable, and yet I still put it down after only a couple of days, frustrated with the slow pace. Now, a little older, working a corporate job, managing chronic conditions, once again confined to my teenage bedroom in my parents’ house after a long series of illnesses and mental health episodes, I finally get it, and it’s so wonderful.

Once you’ve customised your character to your liking, the plot of the game sees you working in a cubicle for, essentially, the game’s antagonist, the Joja Corporation. From the logo, it’s an obvious dig at Amazon, with a bit of Coca-Cola and Wal-Mart thrown in for good measure. They seem to have a monopoly on almost everything, in fact, you can fish up pollution in the form of broken CDs from the rivers or ocean, and the description of the item reads that it’s a JojaNet 2.0 installation CD, and that millions of them must have been produced. Dystopian indeed.

There’s green and red lights indicating whether employees are permitted to “work” or “rest”, and as we pan over to see the player character, on the next desk over, one poor worker has even been reduced to a skeleton. Our late Grandfather is shown giving us a sealed envelope prior to this, and we’ve been instructed to open it only once the grind of modern life becomes too much for us, and in this moment, we reach into our desk drawer and open the envelope. Enclosed is the deed for a small cottage, and a large plot of land, named by the player - I chose the name Patchouli. It feels that this escape is aimed not only at the player character, but to the player themselves, and, if this was Barone’s aim, he has utterly triumphed. It takes maybe a few weeks to a season of in-game time to get used to all the mechanics, and for the gameplay loop to take shape, and this gameplay loop is so very satisfying. Pretty soon, you’re utterly zenned out. Any real life anxieties and woes forgotten, you become one with your farmer. You’re thinking only of what your next goal within the game is, helped by the myriad of skills to learn, including fishing, mining and combat. There’s always something you can be doing, and each task you complete, whether donating items to the Community Centre, more on that later, or selling produce or artisan goods, unlocks more items and mechanics. There’s even arcade games to play, primarily the infamously difficult Journey of The Prairie King. I figured it was impossible, until I realized I could use the right analogue stick to shoot. I still haven’t gotten past the first wave of zombies, though.

That isn’t to say that playing Stardew Valley is an intense experience. Far from it. There are no time limits, and you can complete any assigned tasks, either generated organically through gameplay, through reading letters in the post, at your own pace. In the middle of Summer of Year 1, for example, one of the townspeople will ask you for a pale ale - an artisan product created by growing hops and placing them in a keg for several days. At this stage, it’s a real ask for the player to have obtained either of these items, but the task remains until it’s fulfilled. No hurry. There are some tasks, however, that appear on the bulletin board, with a time limit, usually of a couple of days. You’re offered a monetary reward for these, however, there’s no penalty for not completing them. In fact, there aren’t many penalties for anything at all, with the exception of running out of energy, or health from being attacked by monsters in the mines, or by not making it to bed by 2am.

The primary goal of the early game is to fix up the local community by donating items you’ve foraged, farmed or fished to small, adorable little creatures called Junimos, referred to as the keepers of the forest. When humans abandon a place, the Junimos move in. Think the Soot Sprites from Studio Ghibli films. By working towards collecting items of goods in the dilapidated Community Centre, gradually, the broken-down parts of town are rebuilt by the Junimos. Public transport services resume and broken bridges are fixed. I think this is a huge part of Stardew Valley’s appeal, the ability to give something back to the community, in an increasingly individualistic society, one in which we’ve lost sight of our local communities in favor of aligning ourselves with, and crafting our identities, based our allegiances to multinational conglomerates. There is, however, the option to go a different route to this. To the East of the town, lies a hypermarket called JojaMart, part of the aforementioned Joja Corporation; the players’ previous employer. You do have the option to purchase a Joja Corp. membership, and when this option is chosen, each repair to the community can instead be purchased for a hefty sum, the work carried out by underpaid and overworked Joja employees as opposed to the whimsical Junimos, but it’s entirely your choice.

By the end of my first year at Patchouli Farm, I’d managed to reach the bottom of the mines, (Level 120), set up a mushroom cave, generate over 200k in revenue, obtain a cat called Miffy, three chickens and two dairy cows. Raising animals is not only profitable, but more importantly, emotionally rewarding. You can name your animals; I chose all names beginning with “M”; Mindy, Mandy, Molly, and a cow called Mootilda, before I ran out of names and called one of my cows Maddy Jr. You’re encouraged to interact with them once per day to keep them happy, and this increases the quality of the milk and eggs they produce. Whilst in the real world, I’m morally opposed to humans’ exploitation of animals for food or clothing, in the fantasy world of Stardew Valley, there’s no artificial insemination or genetic modification. Milking cows increases your relationship with them, even, and they magically produce milk without even having to give birth. There are no meat products, aside from fish and seafood, in the game, either, and fish are treated more as objects than animals. This way, I have absolutely no reservations about spending my whole day fishing or milking cows. You also have the choice between a farm cat and a farm dog, and can pick from three designs of each. I chose a grey cat in the absence of a black one, and they don’t really do anything except hang around, but if you fill their water bowl with your watering can and pet them daily, soon enough, you’ll get the cutest notification in the world.

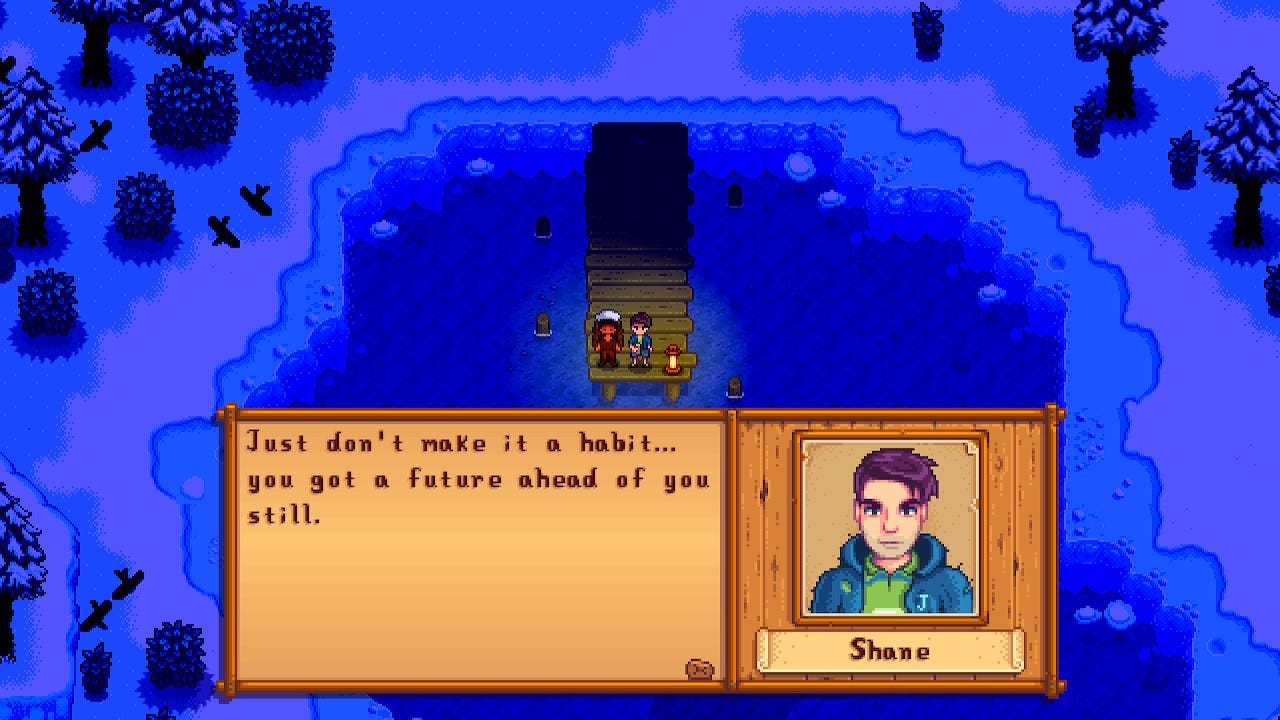

Pelican Town is absolutely brimming with compelling characters for you to befriend or romance, or not. Your relationships with the townsfolk increase slightly each time you speak to them, and can be either positively or negatively affected by the gifts you choose. As you get to know each of them, a picture of their personal nuances and story is slowly pieced together, and the majority of them are incredibly well developed. Take the character of Shane, for example. He’s a guy in his thirties who works stacking shelves at JojaMart, and spends each evening in the Stardrop Saloon, the local pub. When you first meet him, he comes across as rather mean and standoffish, but as you get to know him, his story becomes apparent. He suffers from severe depression and drinks to self-medicate. In one cutscene, he offers you a beer, and comments on how fast you drink it, before telling you, “don’t make it a habit. You’ve got a life ahead of you, still.” Eventually, with the help of the player and Harvey, the town’s doctor, Shane goes to therapy and begins to heal. It’s very sweet.

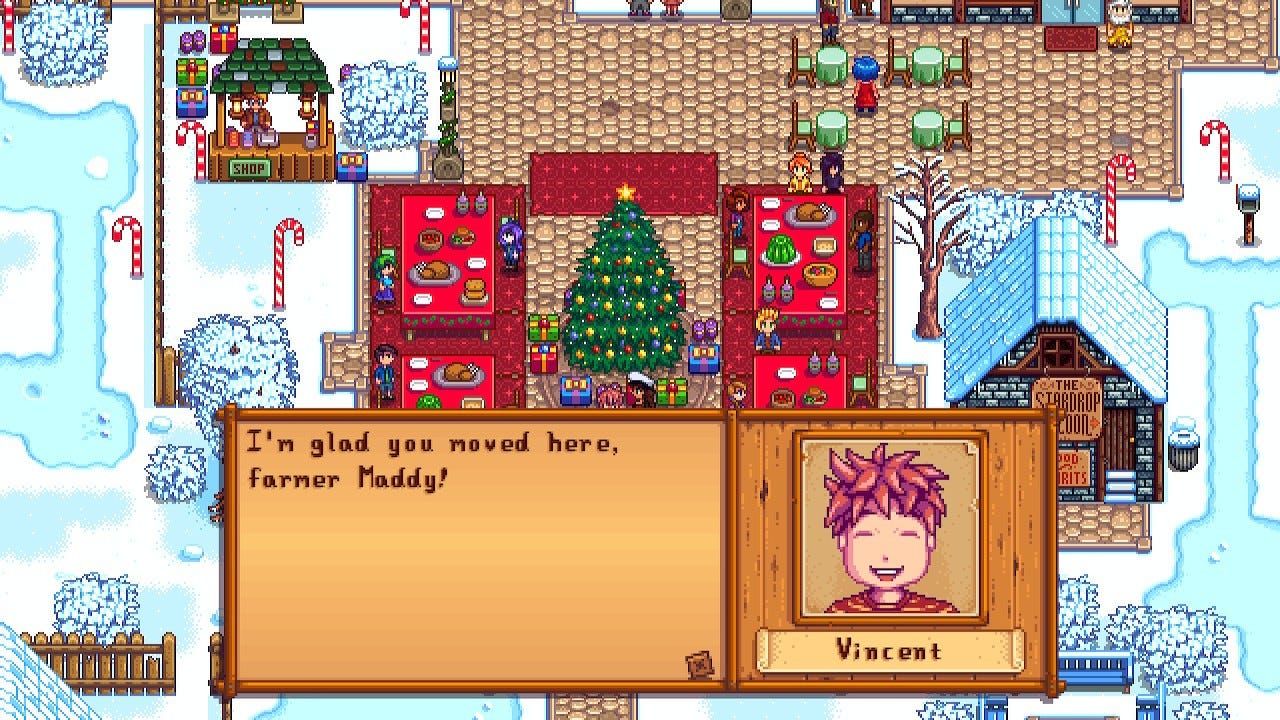

Community events are a major part of the year’s calendar, with festivals such as the Stardew Valley fair (Harvest), Spirit’s Eve (Halloween) and the Feast of the Winter Star (Christmas). For the latter, you receive a letter in the post disclosing your secret gift recipient, like a Secret Santa. My recipient was Emily, a slightly hippie-dippy rich girl I admittedly have a soft spot for. She’s into crystals so I gave her an amethyst I’d saved from the mines. My gift giver, though, was Vincent, a small boy, and his dialogue was just so adorable!

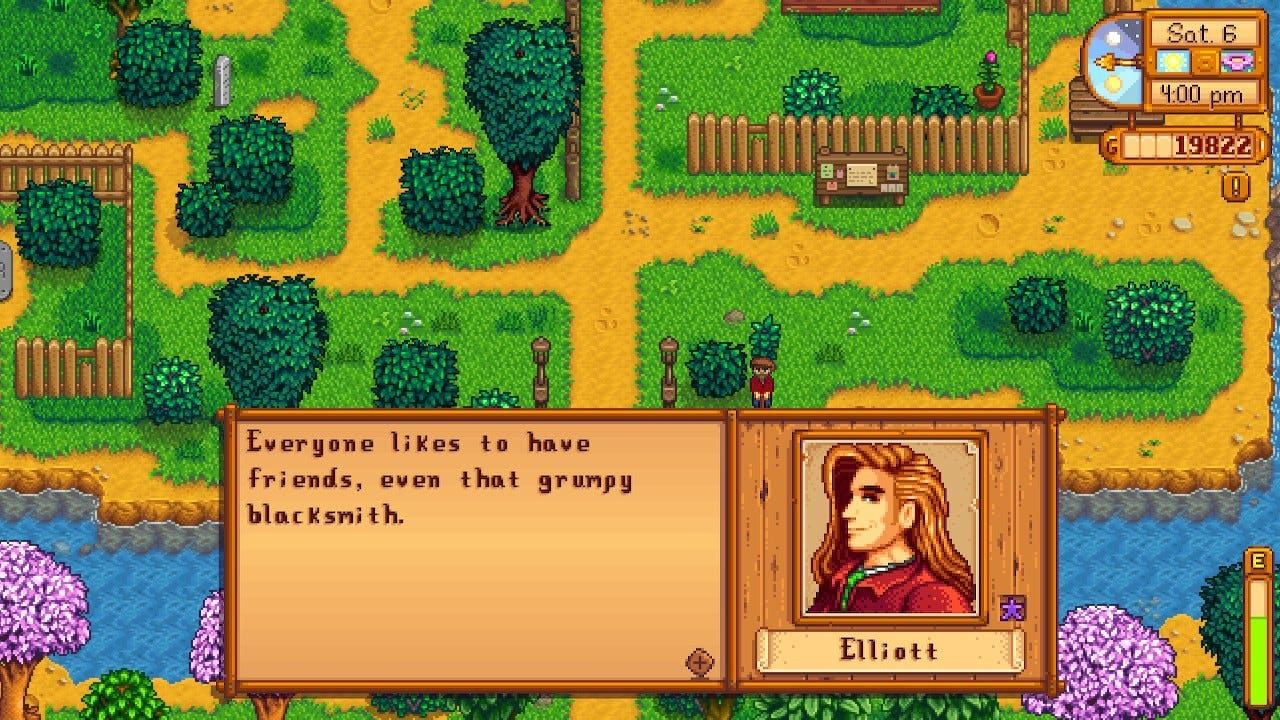

In terms of marriage candidates, there was only one potential partner that made sense for me. In a little cabin on the beach lives an older bachelor who’s somewhat of a hermit, by the name of Elliott. He’s a writer, and he’s struggling for inspiration, until he meets you. His character sprite has him as a nineteenth century dandy, always impeccably groomed. Like me, he’s a dreamer, but isn’t quite sure how to accomplish those dreams. He’s not really gotten that far. It’s often said his character design is Fabio-ish, based on the covers of old bodice rippers, and his portrait when spoken to leans into this quite heavily. He’s the only one drawn from the side, and I must admit that this design was a little off-putting to me at first. Whilst long-haired men are my weakness, there needs to be that streak of effeminacy, which at first Elliott seemingly lacked, until I began reading much of his dialogue. He’s a classic romantic, and knows how to make you feel special and loved, both as a friend and later as a romantic partner. He’s very sweet, and despite his isolation from the rest of town, he sees the good in everyone, and has an almost universally positive outlook. Take when he discusses Clint, the blacksmith. Clint is generally a disliked character in the Stardew Valley community, with many viewing him as standoffish at best, and comparing him to an incel at worst, when he's simply shy and awkward. Elliott says of him, “Everyone likes to have friends, even that grumpy blacksmith”. He recognises Clint’s need for human companionship to come out of his shell, or, well, geode.

Well, with that, I can’t wait much longer to get back on with working on my farm. Until next time.

Great article x